Managing Unique Coastal Rangelands

By Robert Fears

Coastal grazing management has its own unique set of challenges, which are addressed in a publication written by Dan Caudle and David Daigle.

The title of the publication is “Prescribed Grazing – A Management Tool for Wetlands.” The publication was distributed as a supplement in the June 2016 issue of The Cattleman magazine to Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association (TSCRA) members who reside on the Gulf Coast. For those of you who didn’t receive the supplement or haven’t found time to read it, a synopsis of the information comprises a major part of this article.

Flatwoods, coastal prairie and coastal marsh can provide excellent grazing in the southeastern states if managed properly.

Management of natural resources is a complex issue but is especially challenging for wetlands due to political, environmental, social and cultural influences.

Management is further complicated by reduced or discontinued disturbances by natural forces, including fire and grazing, which were key to the development and maintenance of these natural ecosystems.

Descriptions of the ecosystems

The terrain of the Flatwoods is relatively flat with intermittent natural mounds and ponds. Historically, Flatwoods were dominated by longleaf pine covering almost 90 million acres in 9 southern states, stretching from southeast Virginia to southeast Texas.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, almost all the merchantable longleaf trees were removed.

Many of the clear-cut areas were planted to introduced forages or loblolly, slash or shortleaf pine. Today, less than 4 percent of the original longleaf pine habitat remains and a significant portion of those acres are in a deteriorated state due to neglect or mismanagement.

The Gulf Coast Prairie is a relatively flat, virtually treeless tallgrass prairie. It is the southernmost extension of tallgrass prairies in the central and midwestern states and contains many of the same plant species.

The Gulf Coast Prairie also produces a host of additional grasses and forbs (herbaceous broad-leaf plants).

Major differences in the 2 regions are the Gulf Coast Prairie’s higher humidity and a greater amount of rainfall. In transitional areas where prairies grade into marsh, Gulf Coast Prairie becomes wet prairie with shallow water on or just below the soil surface.

Gulf Coast marsh is a dynamic and ever-changing landscape that constantly struggles with the ocean and forces of nature.

Tidal surge, flooding, ponding, saltwater intrusion, subsidence and hurricanes are the driving forces shaping this ecosystem by creating shallow bays, estuaries, marshes, dunes and tidal flats.

Coastal marsh ecosystems are low-lying, flat to concave areas with shallow depressions, occasional low ridges and intermittent areas of open water. Elevations range from sea level, where the marsh meets the Gulf of Mexico, to as much as 10 feet in its upper reaches, where it grades into the coastal prairies and cheniers (sand or shell beach ridges).

Marsh soils are fertile and support a dense growth of vegetation, primarily grasses and grass-like plants including sedges and rushes.

The fluid marsh is too soft to support cattle, but the firm marsh can support them and provides excellent range.

Determining stocking rates

The first and most important consideration before implementing a grazing management program on any area is stocking rate. Initially, use a conservative stocking rate to account for variables and unforeseen circumstances. If the stocking rate is too optimistic, it could result in significant long-term degradation of the vegetation. It is difficult, if not impossible, to compensate for early overstocking.

Stocking rate refers to the number of animal units that are grazed on a pasture or range.

Relative to beef cattle, an animal unit is a 1,000-pound cow. Carrying capacity refers to the maximum number of animal units that an area will support for a specified length of time without detrimental effects on vegetation and other natural resources.

Grazing areas require continual monitoring because carrying capacity changes. It can increase or decrease due to amounts of rainfall and other environmental factors. Initial stocking rates should be conservative enough to allow for unfavorable growing conditions.

Carrying capacity monitoring is a way to determine if stocking rates need to be reduced to avoid potential long-term detrimental effects on the vegetation and other natural resources.

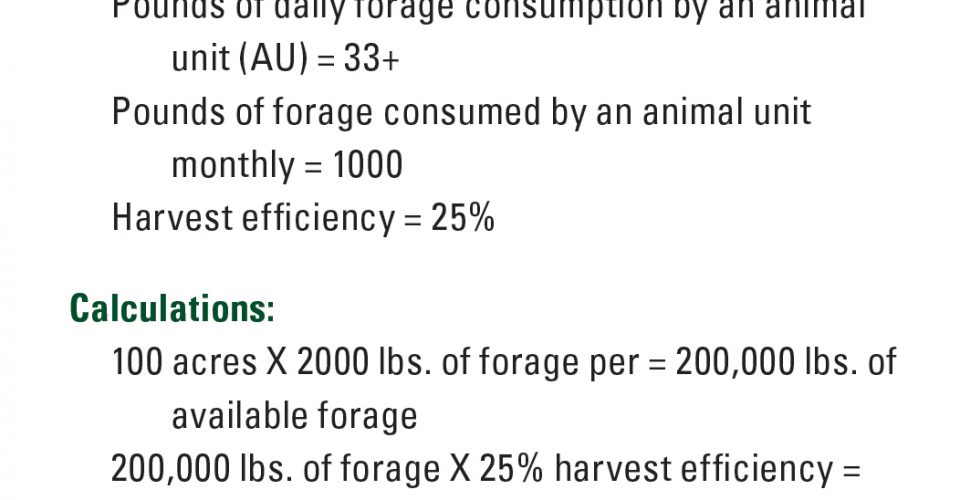

Several factors determine proper stocking rate, including the number of acres in a grazing unit, amount of herbaceous forage produced per acre, amount of forage consumed by an animal unit and harvest efficiency of the grazing animal. Flexible stocking rates are necessary for accommodating multiple resource objectives, variable weather conditions, temporary circumstances or natural disasters such as droughts, floods or hurricanes. In areas where wildlife is a concern, stocking rate and grazing intensity should always allow for their needs. An example of a stocking rate calculation is shown in Figure 1.

The most accurate and time-consuming method of determining pounds of herbaceous forage per acre is to clip and weigh palatable forage from a representative number of small plots, average the weights, and adjust the total to a per acre basis.

A quicker, yet accurate method is use of a measuring stick to measure plant height and estimate forage production. After one of the 2 methods is used several times, many people learn to estimate available forage just by walking the pasture.

Numerous studies by universities, research organizations, livestock nutritionists and others have shown that mature cows and bulls consume approximately 2.5 to 3.0 percent of their body weight daily, depending upon their physiological condition and quality of forage. A good rule of thumb is to assume that a mature cow or bull consumes an amount of forage equal to its body weight each month.

Harvest efficiency refers to the amount of herbaceous forage removed from the pasture by grazing, trampling, bedding and feeding areas, and dung and urine deposits.

The standard rule of thumb for native grassland management is to graze no more than 50 percent of the forage. That percentage does not account for vegetation not consumed because it is overly mature, unpalatable, overlooked, unavailable or inaccessible for grazing. Harvest efficiency is only about 25 percent on diverse native grasslands where continuous grazing or non-intensive grazing occurs. It can increase dramatically in intensive grazing systems where stocking rates and stock densities are higher and livestock graze more uniformly.

Grazing management techniques

Once a safe initial stocking rate is determined, the next most important decision concerns the need for deferment (rest) from grazing. Native plant communities require disturbances such as fire, grazing, haying or mowing. After disturbance, they need adequate time to rest, regain vigor, regrow and reproduce. The 2 critical factors to consider are length and timing of rest periods.

Length of deferment periods varies with vegetation type, season of the year, and growing conditions. In the Gulf Coast region, the fast-growth period is generally from April through June. During that time, most warm-season grasses and forbs need adequate rainfall and a minimum of 21 days following defoliation to adequately recover. As the summer progresses, the needed recovery period normally lengthens to about 24 to 28 days. From late September through November, plant growth slows noticeably and most herbaceous species need a minimum of 30 to 40 days to recover.

Time deferment periods to allow for seed production and/or vegetative reproduction, wildlife habitat needs such as nesting and escape cover, seedling establishment and maintenance of adequate vegetation to facilitate prescribed burning. For optimization of benefits in a diverse plant community, stagger rest periods from year to year and season to season.

While vegetation needs periodic rest from grazing and other disturbances, inadequate fire frequency or excessively long periods of rest are detrimental to most ecosystems because they release or encourage woody plants, which gain height dominance over grasses and forbs and capture their sunlight. Excessively long deferment periods also allow vegetation to overly mature and begin deteriorating.

Grazing periods are the next consideration. Number of grazing days per grazing unit is based on amount of forage produced, number of grazing animals and stock density. Plan grazing periods on forage types and their seasonal growth patterns. Forage quality at various times of the year is also a key factor. Limit length of grazing periods to avoid repeated consumption of the same plants.

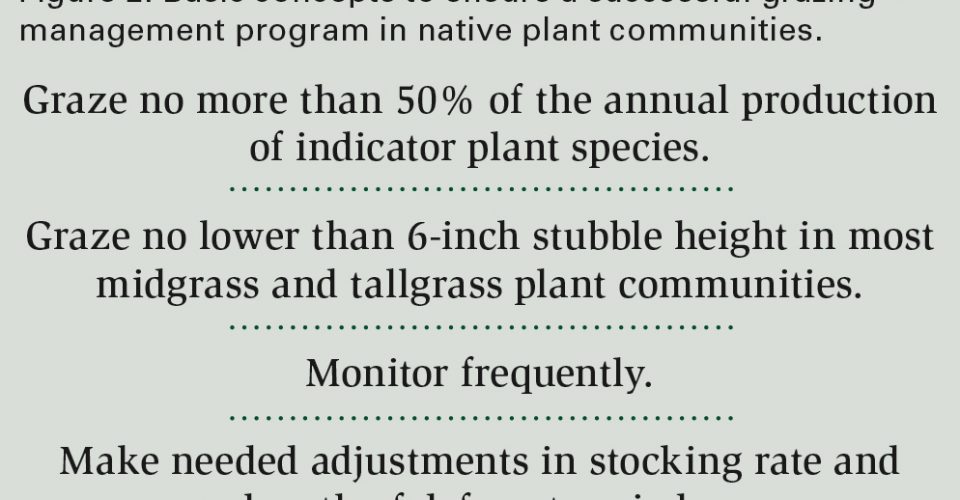

To be successful and sustainable, a grazing management program must meet the physiological needs of the vegetation, nutritional requirements of the animals and enterprise objectives of the owner/manager. Planned grazing and rest periods must be flexible and determined primarily by the physiological stage of the vegetation with respect to current and expected future weather and growing conditions. Concepts utilized to ensure a successful grazing program are found in Figure 2.

Only a small percentage of the Prescribed Grazing publication is discussed in this article. Complete copies of the publication are available from The Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) at https://shop.brit.org/products/prescribed-grazing or by contacting Dan Caudle at jonestar5@charter.net.

“Coastal Grazing” is excerpted from the November 2017 issue of The Cattleman magazine.